- September 22, 2021

- Organization for the Prevention of Violence

Foreword by our Executive Director

After three years of program development and two years of operations, we are proud to share our data and findings from the Evolve intervention program. The Organization for the Prevention of Violence (OPV) holds a commitment of openness and transparency to the communities we serve. This was the impetus for the “First Two Years” report, which tells a complete story about our operations: who we aid, the services we provide, and an honest account of our successes and challenges.

Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE) remains a work in progress. By sharing our experience in delivering intervention services, we aim to contribute to the ongoing development of a nascent area of human service and a community of practice. Evidence-based and practitioner-oriented research is central to our work and, we believe, the success of P/CVE.

John McCoy, PhD | Executive Director

Suggested Citation

Organization for the Prevention of Violence (September 2021). “Evolve Program: The First Two Years”. Edmonton: Organization for the Prevention of Violence.

This report was developed and created by the Organization for the Prevention of Violence and published on September 22, 2021.

This project is generously supported by:

Table of Contents

About the OPV

The Organization for the Prevention of Violence (OPV) was established in 2016 with the vision of creating an evidence-based preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE) program in Alberta. This included both research and psycho-social intervention services.

This initiative arose from the recognition that Alberta was not immune to hate or terrorism and was disproportionately impacted by certain forms of extremism.1 With the support of Public Safety Canada, the Canada Centre for Community Engagement and Prevention of Violence, REACH Edmonton Council for Safe Communities, and the City of Edmonton, the OPV developed the Evolve Program. Evolve is a specialized, inter-disciplinary intervention program aimed at providing direct support to individuals involved in hate or extremism, their affected family or friends, as well as victims of hate incidents.

Prior to launching the Evolve program, the OPV invested several years into research, program development, and stakeholder consultations. Through these processes we established community and stakeholder support that proved to be essential for the initial success of the program. The OPV also solidified partnerships with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Edmonton Police Service (EPS), REACH Edmonton Council, the City of Edmonton, and a host of community-based and non-government agencies.

About the Evolve Program

Launched in April 2019, Evolve is a psycho-social intervention program that delivers services to individuals involved in extremism or hate-motivated violence, and/or their families. Services are free, confidential and personalized.

The Evolve program prioritizes a relationship-based model of service delivery and trauma-informed care. The multi-disciplinary team is currently composed of a forensic psychologist, two social workers, and three specialized mentors: two former members of the far-right movement and an Islamic scholar. The intervention team uses their collective experience and knowledge of local services to:

- assess needs, risks and protective factors;

- plan and deliver intervention services; and

- mobilize necessary resources for program participants.

The team meets regularly for case consultations and coordination. Evolve staff also participate in the Virtual Partnering in Practice Project, a peer-support case discussion forum for Canadian P/CVE programs led by the Canadian Practitioners’ Network.2

Participants in the Evolve program can access a variety of services, including personal, family and religious counselling, mentoring, advocacy, crisis management, addiction support, and help with basic needs. The Evolve program also helps participants access and navigate bureaucratic support systems, such as financial assistance, employment support, child welfare services, legal aid, and the justice system.

Adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic

After only one year of operation, the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing public health restrictions forced the Evolve program to quickly adapt its service delivery method. Caseworkers adopted the use of various video and messaging software designed to support virtual intervention programming, all the while providing in-person services when necessary. Despite the pandemic, the Evolve program continues to receive referrals, welcome new participants, and provide services to existing participants.

Service Recipients

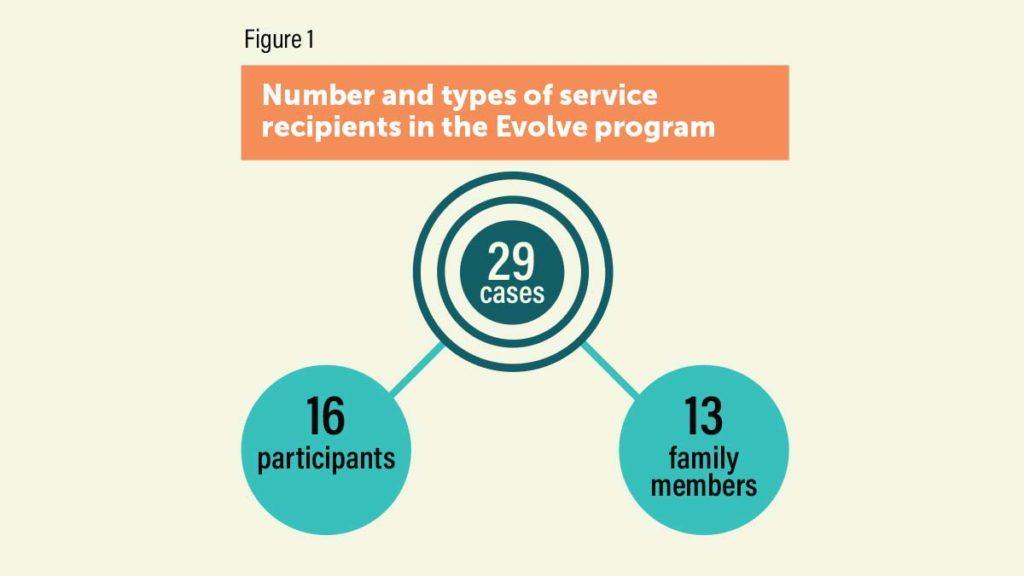

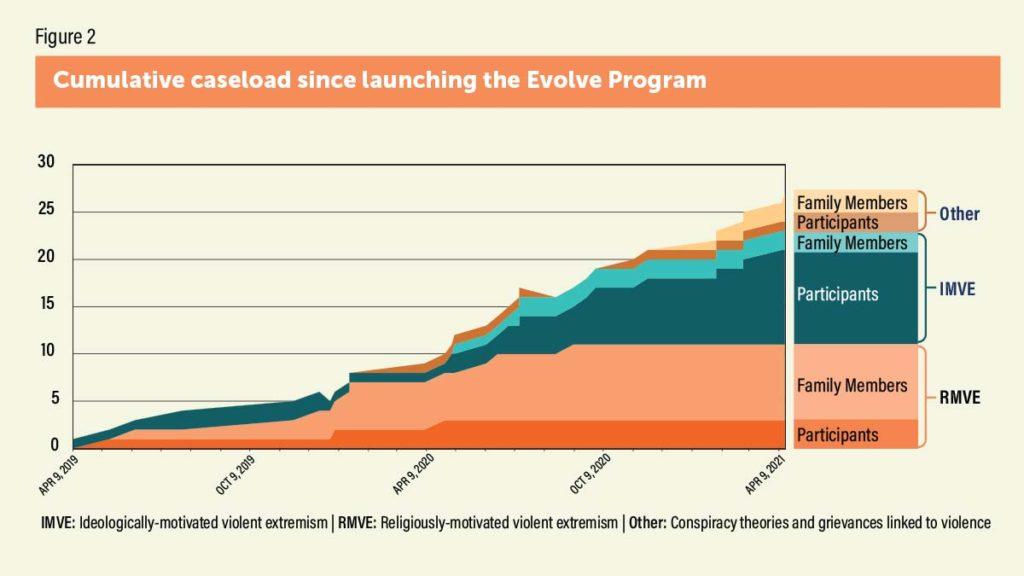

In its first two years of operation, from April 2019 to April 2021, OPV’s Evolve program offered services to 29 individuals.3 These service recipients fall into two categories (see Figure 1).

The first category includes individuals who currently espouse, or have previously held, beliefs related to extremist ideologies that may lead to violence; they will henceforth be referred to as participants.

The second category consists of family members of individuals who espouse extremist or hateful beliefs that may lead to violence. In some instances, family members are seeking support to encourage their loved-one to disengage from violent extremism. In other instances, family members are preparing for the eventual return, either from abroad or from prison, of a loved-one who engaged in violent extremism.

“Having access to [an Islamic scholar] is like having a professional friend. He has been sent by God.”

-Evolve Participant

Participants

At the time of its second anniversary, the Evolve program was providing services to 14 participants, while another two participants were no longer in the program.

Of these 16 participants, 14 were men with an average age of 33, while the remaining two participants were women and significantly older.

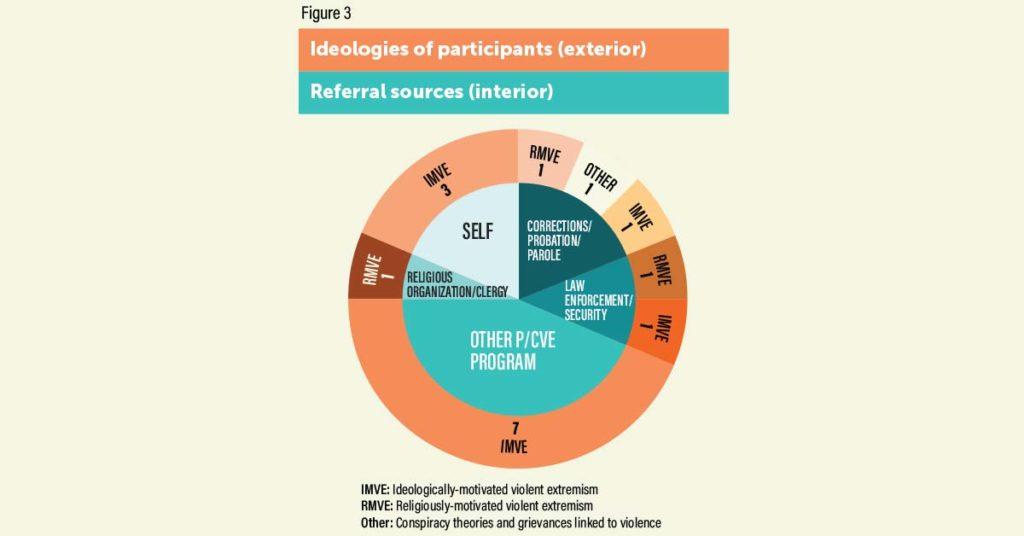

A little less than half of all participants were referred by another P/CVE program. The majority of participants espoused some form of ideologically motivated violent extremism (IMVE)4, while the second most prevalent ideology was religiously motivated violent extremism (RMVE).5

Participants came to the Evolve program through several different referral sources. Figure 3 details these referral sources while specifying the ideology espoused by the participants.

It should be noted that the program received few referrals from police, which matches the experience of other community-based P/CVE programs.6 However, this contrasts with government-led programs, namely Channel in the U.K. which receives many referrals from the police and other public services.7

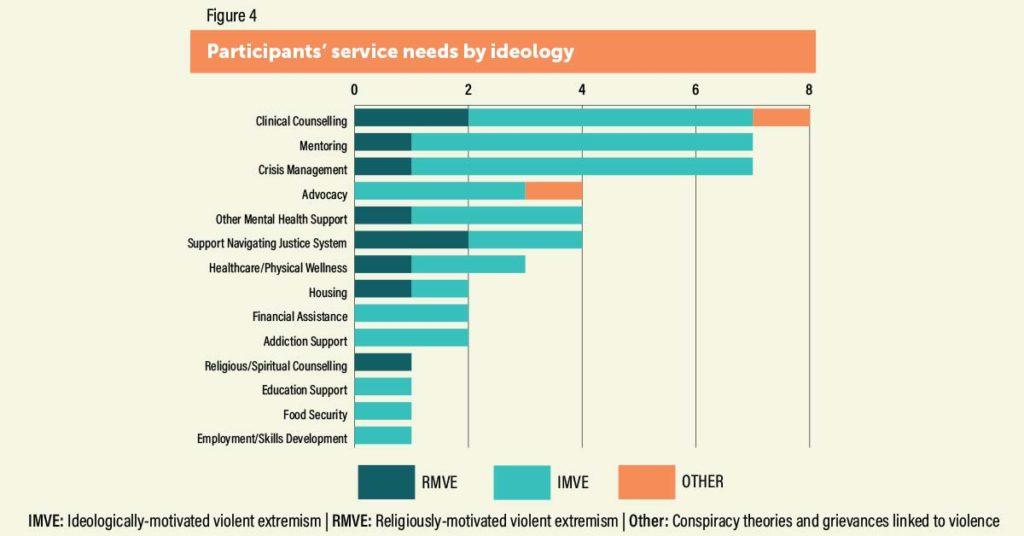

While each participant joined the Evolve program with a unique set of life experiences and needs, the greatest needs overall were for clinical counselling and mentoring.

Figure 4 provides a detailed overview of participants’ most important needs as determined by Evolve staff through consensus. To be clear, some participants did not receive the services they reportedly needed. This can happen when, for example, a team member determines a participant could benefit from clinical counselling, but that participant declines this service. In most cases, however, participants have welcomed recommended services and frequently collaborate with Evolve staff to identify their needs and goals.

It should be noted that the type of services needed by participants are sometimes beyond the scope of conventional psycho-social interventions and sometimes require team members to have a “whatever it takes” approach.

Helping participants find housing, facilitating tattoo removals, advocating for changes to federal government policy, negotiating interactions with foreign law enforcement, and discussing complex theological or ideological concepts are just some examples of services rendered by Evolve staff as part of the broader effort to help participants disengage from violent extremism. The experience of the Evolve program to date demonstrates the complex needs that differentiate P/CVE programming from adjacent forms of human service work.

Family Members

In its first two years of operation, the Evolve program delivered services to 13 family members —representing 10 distinct families— of individuals who espouse extremist or hateful beliefs that may lead to violence. Half of these families were seeking help for a relative who was involved with RMVE. The remaining families were concerned with relatives involved with IMVE ideologies, or other forms of extremism, such as conspiracy theories linked to violence.

Notably, 12 of the family members were women. Their familial relationships towards the radicalized individual in their family were diverse: mother, sister, spouse, and aunt. While the overall sample remains too small to assume this overrepresentation of women might also occur in other P/CVE programs, it is nonetheless a striking finding. At the very least, this potential gender effect warrants further study into, for instance, whether women are more likely than men to seek help for a family member involved in violent extremism. Anecdotally, OPV staff have intervened with several female members of a family who welcomed receiving services from Evolve, while the male members of that same family were hesitant about agreeing to formally participate in the program.

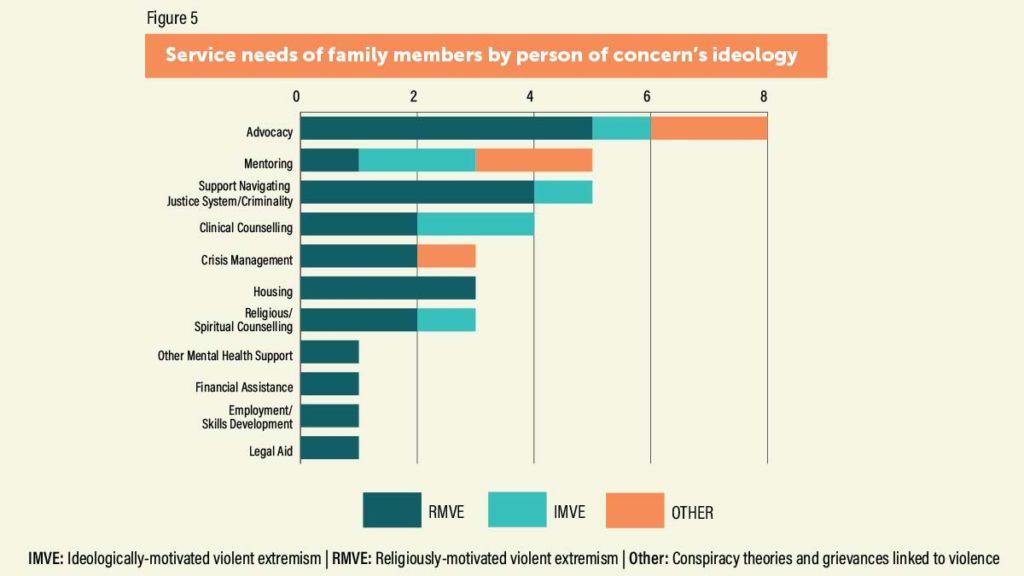

As illustrated in Figure 5, the greatest need for family members involved in the program was for advocacy.

In some cases, this advocacy took the form of helping family members navigate the complex political and legal issues associated with the possible repatriation of Canadians currently detained in Northeastern Syria. To date, there has been little progress on this issue, despite repeated calls by international non-government organizations like Amnesty International & Human Rights Watch.8

In other cases, the Evolve staff helped family members develop stronger self-advocacy skills to navigate government bureaucracies such as the criminal justice system.

The Challenges

In its first two years of operation, the Evolve program achieved its goals of enlisting individuals requiring specialized intervention or support services and delivering those services. For several participants and family members, the Evolve program proved to be the only resource available after other social service providers were unable or unwilling to help address their needs created by their own, or their family members’, involvement with extremist ideologies.

While Evolve team members and service participants experienced a great deal of success, for example, in addressing identified needs and enhancing protective factors against radicalization to violence, the program did also encounter challenges. These challenges are worth noting as they inform how the OPV adapts its Evolve program to the changing landscape of violent extremism.

Challenge 1: Not-so-voluntary participation

The Evolve program was designed to be voluntary: participants would freely consent to receive services. Yet, the voluntary nature of service participation has emerged as an unexpected challenge.

As referrals were made by law enforcement and other government agencies, some participants have felt compelled to participate in the Evolve program. In other cases, parole boards have mandated individuals to participate, leaving them with no other realistic choice, since failure to join the program could result in

their incarceration.

These circumstances can diminish motivation to participate in the program, lead to heightened distrust of the Evolve staff, and undermine the rapport necessary for a successful intervention.

While these situations challenge the relationship-based approach of the Evolve program, they are not insurmountable, nor are they unique to the OPV or to P/CVE in general. Other service providers face similar issues dealing with mandatory participation, such as in programs focused on domestic violence, addiction, gang involvement, and impaired driving.

In P/CVE cases where participation is perceived as mandatory, establishing rapport can take a long time. We have found that maintaining transparency about the relationship that the OPV and the Evolve program has with police and the justice system are essential to developing a trusting relationship with the participant.

We make it clear to participants that the Evolve program is not an extension of the justice system, and that our team does not execute the conditions set out by police or probation orders. However, in certain cases the OPV does report to the relevant authority, for example a probation officer, about whether the participant is maintaining contact and minimal levels of participation with the Evolve program.

These and other parameters are candidly discussed and agreed upon with the participant. That said, the OPV does remain realistic about mandatory participation: some participants may never reach the level of trust and vulnerability that others do, and in some cases, a participant’s unwavering ideological commitment creates an insurmountable barrier for Evolve team members.

Challenge 2: The boundaries of violent extremism

Radical Communities

The first type of participant stems from newer radical communities that have emerged in recent years, specifically the Q-Anon movement and the Incel community. While individuals from these communities have conducted violence and even acts of terrorism, it should be recognized that the majority of Incels and Q-Anon adherents do not engage in —or even support the use of— violence.9

In contrast, the vast majority of Salafi-jihadists, Neo-Nazis, and accelerationists consider violence as an established means of addressing grievances and a central tenet of their ideology. Therefore, requests to provide support to people involved with the Q-Anon movement and the Incel community raises a dilemma for OPV.

On the one hand, providing support to individuals who are not on a path towards violence contradicts the stated objective of the Evolve program, which is to counter violent extremism. On the other hand, members of these radical communities often have similar grievances and psycho-social needs to individuals involved in violent extremism, making the specialized services of the Evolve program a natural fit for individuals looking to disengage from these beliefs systems. In some instances, these individuals have been denied service or have experienced stigma after reaching out to health and social service providers, making the OPV the only organization willing and able to help. As a consequence, the OPV has decided to accept individuals who adhere to Incel and Q-Anon belief-systems, and their family members, in the Evolve program for the foreseeable future.Family Members

The second type of participant are family members who have concerns about an individual’s extremist beliefs or behaviors. The challenge here occurs when the individual of concern does not ultimately join the Evolve program, leaving family members —who do not espouse extremist ideologies— as the main clients in a program designed to counter violent extremism. Here again, because of its specialized services, Evolve may sometimes be the only program able and willing to help families of individuals involved in violent extremism, hence why the OPV has chosen to deliver services to these family members.Next Steps for the Evolve program

Expanding Evolve’s geographic remit

Initially, Evolve was intended to work primarily with individuals in the greater Edmonton area. However, as Evolve became more widely known, participants were being referred from smaller population centres in Alberta.

To address this demand, the OPV is currently expanding and redeveloping its training products, together with the City of Edmonton and the Edmonton Police Service’s Resiliency Project, to better cater to social service providers and educators in smaller cities and towns across Alberta.

Additionally, the OPV is working to establish new partnerships with organizations in these communities to build a broad network of

P/CVE actors. The aim is to develop a latent intervention capability in communities across Alberta than can provide local support should cases arise.

The OPV has also provided services to a number of individuals outside Alberta. In some cases, these individuals specifically sought out members of the Evolve team due to their public notoriety. In other cases, we received referrals from locations that do not have a P/CVE program. To date, the Evolve staff have worked to manage these cases virtually with, if available, local social service providers. Continuing to develop and formalize this mode of intervention is a priority for OPV.

Expanding sources of referrals

One noticeably absent referral source for the Evolve program is the education system. Research conducted on a P/CVE program in the U.S. suggests students might be reluctant to report concerns about extremism to school authorities.10 The OPV is planning on creating materials to raise awareness of the Evolve program among local students and education professionals.

Tracking services, progress, and feedback

The OPV is currently developing methods to measure the impact and progress of the interventions delivered by the Evolve program. These measures will help us identify trends during the course of service delivery. Most importantly, these measures will help us understand how Evolve is helping participants over time, what needs to improve, and what might be missing in our program. One of these methods will entail asking participants to regularly complete a short questionnaire, which will ensure our services remain focused on their needs.

If this report interested you, please share it with your network or browse our other publications.

Powered By EmbedPress

Footnotes:

John McCoy, David Jones, Zoe Hastings (April 2019). Building Awareness, Seeking Solutions: Extremism & Hate Motivated Violence in Alberta. Organization for the Prevention of Violence: https://preventviolence.ca/publication/building-awareness-seeking-solutions-2019-report/

This forum, led by the Canadian Practitioners Network (CPN-PREV) and Dr. Ghayda Hassan, has played an essential role in bringing together Canadian P/CVE professionals and programs.

Beyond its first two years of operation, the Evolve program continues to experience a steady influx of referrals. At the time of publishing this report (September 21, 2021), team members were providing services to 37 individuals, of whom 20 were participants and 17 were family members.

IMVE is the acronym for ideologically motivated violent extremism, a term recently used by the Government of Canada to designate a range of ideologies that were previously referred to as “far-right extremism” and “far-left extremism”, and include xenophobic violence, anti-authority violence, and gender-driven violence. For more information, see: https://www.canada.ca/en/security-intelligence-service/corporate/publications/2020-public-report.html

RMVE is the acronym for religiously motivated violence extremism, a term recently used by the Government of Canada. For more information, see: https://www.canada.ca/en/security-intelligence-service/corporate/publications/2020-public-report.html

For example, see: B. Heidi Ellis, Alisa B. Miller, Ronald Schouten, Naima Y. Agalab & Saida M. Abdi (2020): The Challenge and Promise of a Multidisciplinary Team Response to the Problem of Violent Radicalization. Terrorism and Political Violence, DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2020.1777988

U. K. Home Office (November 2020). Individuals referred to and supported through the Prevent programme.

England and Wales, April 2019 to March 2020. Retrieved from bit.ly/3tDklyt.Human Rights Watch (June 2020). Bring Me Back to Canada: Plight of Canadians Held in Northeast Syria for Alleged ISIS Links. Accessed through https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/06/29/bring-me-back-canada/plight-canadians-held-northeast-syria-alleged-isis-links

For example, see: Anne Speckhard (January 19, 2021). What Incels Can Tell Us About Isolation, Resentment, and Terror Designations. Homeland Security Today. https://bit.ly/3CszwxN; see also the “backgrounder” by the Anti-Defamation League: https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounders/incels-involuntary-celibates

Michael J. Williams, John Horgan, & William Evans (June 2016). Evaluation of a Multi-Faceted, U.S. Community-Based, Muslim-Led CVE Program. U.S. Department of Justice.